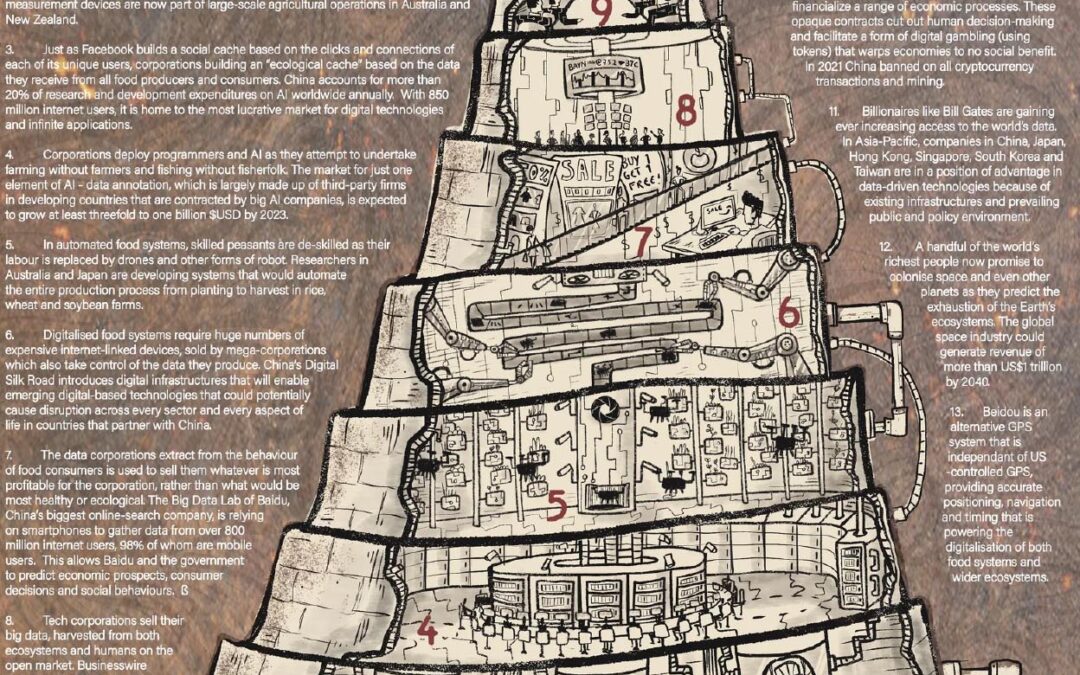

Some of the world’s biggest corporations, including Bayer and ChemChina, are making deals with data giants such as Amazon and Alibaba to turn human behaviour and environmental knowledge into computer code. The ‘artificial intelligence’ they are creating by applying algorithms to this data is being deployed in order to control land and water resources previously controlled by local communities for millennia. Evoking past colonial practices, corporations are now using digital tools to push methods that dominate industrial food systems, such as artificial fertilisers, mechanisation, monocultures and toxic pesticides, onto remaining small-scale farming and fishing operations. Current trends in digitalisation threaten biodiversity, the wider environment and human health, yet there are few challenges to the tech industry’s hype about a ‘fourth industrial revolution’.

Like most industrial technologies, the process of digitalising our food systems and other global ecosystems has appeared as a result of a small number of entrepreneurs and large tech corporations identifying new ways to make a profit. The future of the technology will be based on a series of choices; it is not an inevitable historical process as its promoters suggest. Before we attempt to influence the application of these digital technologies in Asia-Pacific, we need to understand the interests that underlie them.

While most big data investors have interests in other sectors, such as health and education, they envisage food systems as the biggest profiteering opportunity. Some people may not have the means for adequate healthcare or schooling, but everyone needs to put food on the table. These tech titans aim to extract and then use patterns in data to reshape food economies and ecologies and gain monopolistic control to maximise their profits. In this they resemble neo-colonial resource grabbers.

The world’s big tech firms – Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft and Asia-based Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent – are betting on the digitalisation of the food system yielding their investors a high return. All have amassed huge financial assets by implementing their version of the Californian Ideology of the 1990s, ‘move fast and break things’. The rapid acceleration in online food shopping during the Covid-19 pandemic strengthened their hand in persuading some policymakers that they could be trusted with control of global food systems.

Two tech companies, Amazon and Alibaba, are predicted to make USD 30 billion in food sales within the next five years, effectively making them the two largest food supermarkets in the world. But these data giants don’t just see their future in selling food. They want to make money all the way along the chain. Amazon has already invested billions in food warehousing, retail and logistics subsidiaries.

Meanwhile, agrichemical companies like Bayer, Corteva and Syngenta have gambled on a series of mega-mergers with data companies. At the core of these mergers is big data, of which they can capture ever-increasing volumes through collection devices placed in self-driving tractors, drones, sensors in the field and even devices attached to plants and livestock. Every device gathers and transmits data to corporate data centres, which use algorithms to process the statistics and provide what the corporations have dubbed ‘artificial intelligence’ (AI).

Impacts in Asia-Pacific

There are few published estimates of the scale of digitalisation of agriculture in Asia-Pacific. However, the recent activities of Bayer (which acquired agriculture giant Monsanto in 2018) give a strong indication of what could take place globally if this latest wave of corporate expansion continues unchecked.

Developed by Climate Corp, which was acquired by Monsanto in 2013, Fieldview is a form of AI that already gives Bayer control over half of the digital farming market worldwide – currently 60 million hectares in 23 countries. Presented as an app for farmers, Fieldview links over 70 partner corporations on a digital platform that Bayer promises will ‘organise’ data from across all farming operations, combine this with data about weather, soil and markets, and generate targeted ‘prescriptions’ to increase a farm’s short-term productivity.

In Asia-Pacific, different data giants are now making their moves. In India, a group of companies led by Microsoft signed a memorandum of understanding with the government in 2021 to start a pilot project in 100 villages across six states. The memorandum requires Microsoft to create a ‘Unified Farmer Service Interface’ through its cloud computing services. Following the model of Fieldview, this government app, called AgriStack, will coerce farmers into handing over every globule of real-time data about local agricultural conditions and farmer behaviour across India. By harvesting these millions of gigabytes of data, Microsoft will be a step closer to digitalising and thus taking control of the entire Indian food system. This MOU has not been withdrawn, despite the government’s recent repealing of its controversial 2020 farm laws.

Four hundred years ago, by dispossessing people in Asia of their resources and livelihoods, the British East India Company became the first global private corporation, and the most powerful private company on Earth by 1850. Today, tech companies like Microsoft are attempting to do the same through digitalisation, by extracting people’s knowledge and behaviours in relation to ecosystems.

Ecological caching

In order to sell their products, Facebook, Netflix and Google extract every detail of their users’ online behaviour, including their viewing habits, ‘likes’, ‘shares’, and comments, using systems of corporate surveillance that have been called ‘social caching’ – with ‘cache’ being the name for the data collected by web browsers. In the same way, both Bayer (in much of the world) and Microsoft (in India) are now using ‘ecological caching’ – the collection of data relating to every possible aspect of farmers and their environment – to further their next iteration of input-intensive farming, such as industrial monocultures.

The monetisation of data

Unlike physical commodities that increase in value through scarcity, data increases in value as more of it is aggregated. AI turns the ecological cache (see Box 1) collected by a corporation into actionable economic insights. Promotions for farm data platforms take care to depict this information as something an app is merely helping organise, but which still ‘belongs’ to the farmer. Advertisements portray entrepreneurial farmers, smartphone in hand, controlling their own data. But in reality, platforms such as AgriStack will extract the data, which Microsoft receives for free, and aggregate and process it in large data centres using algorithms that have been trained on mega-farm monocultures, such as those that dominate the prairies of the mid-West United States.

Whoever owns these data patterns can then sell them as a commodity to other corporations, such as land speculators, commodity traders, hedge funds and seed breeders. Ultimately, it is not farmers who will gain a useful overview of their fields, but companies like Bayer and its partners – firms like Microsoft – who will gain a detailed digital overview of entire land, water and food flows. The insights from this ecological cache will enable them to better target farmers to persuade them to adopt practices and products that suit the shareholders of mega-corporations.

As a means of enhancing this ecological cache, the digital titans look set to add organic and other eco-friendly farming systems to their stock of big data. It would be naïve to believe that family farmers, ethical co-ops and other small-scale food enterprises can play in the new food data economy on a level playing field. They will fall prey to surveillance, extraction and exploitation by these monopolistic data miners if they join digital platforms.

Big tech dominance

Both AgriStack and Fieldview rely on cloud services to develop their AI capabilities. These will be provided by Microsoft Azure and Amazon Web Services (AWS) respectively. Amazon is currently the world’s most valuable company, approaching the first USD 2 trillion market valuation in history. It derives 63% of its operating profit from AWS cloud services, with digital farming and processing of data as its next major frontier for profits. The new digital entrants into agribusiness are tilting the already unfair power dynamics in the food system towards the dominance of their own AI systems. Amazon’s USD 13.5 billion overall profit in 2020 was almost double the profits of the world’s ‘big four’ sellers of agricultural input – Bayer, Corteva, Syngenta/Sinochem and BASF – combined.

Asia, particularly China, Japan and the so-called ‘Asian tigers’ – Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan – have an advantage in digital and data-driven technologies because of existing infrastructure, capacity and enabling policy environments. Governments and populations in these emerging markets appear to have positive views about the use of advanced digital and data-driven technologies such as those associated with AI. Interestingly, countries such as India, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia and UAE, where people have high levels of distrust for their governments due to reported or perceived corruption, also have positive views about AI.

Four predictions for a digitalised food system

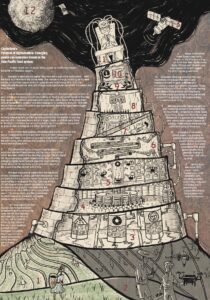

- Collapse of agroecological systems

If people, whether farmers, indigenous hunter-gatherers or other local communities, provide ecological and social caching for mega-corporations, they will be promised a benefit, such as a guaranteed sales price. However, by entering this Faustian pact they would be handing corporations control over what happens to their land and other resources in the forests, lakes, rivers and sea. All the evidence so far is that AI systems rarely work in living systems outside laboratory or near-laboratory conditions. They are likely to endanger the future of both diverse agroecological food systems and industrialised monocultures, the latter being already less resilient.

- Deskilling, displacement, alienation

In a digitalised system, farm workers are removed from their relationship to living things, land and water. Patterns detected by machines relating to biodiversity cannot generate holistic and transdisciplinary understanding of the interactions of humans with nature. Far from being sustainable, the automated mechanisation that is the ultimate objective of digitalisation endangers the very local and indigenous knowledge of ecosystems that underpins the future of humanity.

- Increased energy use for data collection and storage

ETC Group recently estimated that the energy needed to extract and process the data from the US corn crop alone, for just one year, would be roughly equivalent to the entire annual energy use of a country like Nepal or Cambodia.

- Increased extraction of raw materials

Current trends suggest that over the next 14 years, digitalisation could lead to a threefold increase in mining of heavy rare earth metals and even rarer metals like copper. Given the long history of pollution and depletion of water sources, forests, agroecological systems and biodiversity caused by mining for these minerals in the past, we can reliably predict even more devastating consequences of this acceleration of extractive capitalism.

Global tech giants are planning to grab data from farm to fork, undermining the livelihoods of communities which are already struggling with widespread land degradation, pollution of waterways and biodiversity loss caused by industrial agriculture. Based on an extractive capitalist logic, rather than ecological or social understanding, this tsunami of digitalisation threatens to cause a new wave of intensification of agriculture and the legalised theft of resources. We are only beginning to conceive the potential harm to the environment and biodiversity that is likely to follow from what its promoters celebrate as a ‘fourth industrial revolution’.

While it may be too soon to say that digital technologies could never bring ecological and social benefits, it is already clear that approaches based on AI threaten disaster. Yet corporations are currently being allowed – even encouraged – to grab land, water and genetic resources to advance their digitalisation plans without regard for environmental or human impacts. Whether or not their digital technologies work, these corporations can create an investment bubble, make a quick profit, and walk away, leaving the planet even less resilient to the accelerating impacts of climate change.

We need to stop the digitalisation juggernaut and undertake a fundamental rethink of how such technologies are developed and assessed. Otherwise, the ‘next industrial revolution’ may not only bring greater ecological destruction than the previous three, but risk being human civilisation’s last gasp.