How are technologies assessed?

There is no off-the-shelf formula that can be simply applied to the assessment of technologies. Just as it is too simplistic to think of a single technology solving a complex social or environmental problem, so processes of assessment have to address the complexity that underpins communities, ecosystems and issues of justice.

The ETC Group has approached this challenge by helping convene a number of technology assessment platforms (TAPs), each of which are underpinned by a set of values – protection of autonomy, precaution and people’s control; and principles – relating to care, transparency and consent.

TAPs are committed to strengthening initiatives that have been built from the bottom up, such as those initiated by popular and social movements, rather than initiatives organised by elites from the top down, such as expert-led processes of technology assessment. In this way TAPs aim to enable local communities, particularly those groups in society whose knowledge has been marginalised, to take greater control over the process of technology development.

People who can contribute to technology assessment:

TAPs now exist in a growing number of global Regions.

Case studies

Here are some processes of technology assessment in which there has been inclusion of peoples in all their diversities including indigenous peoples, local communities, farmers and fisher folk, as well as popular and social movements.

We call this participatory TA or pTA.

3 examples of pTA processes in the Global South

1) TECLA’s Terminator study (Latin America)

One of the first case studies that the TECLA network decided to document was the case of Terminator technology. These were the invention of “suicide seeds” that could be sold but not used for a new harvest. Officially called a GURT technology (Genetic Restriction Use Technology), they appeared during the late 1990s but early denunciation and broad and continuous international collaboration, involving popular peasant movements, rural workers, women’s and consumer organizations, indigenous peoples’ organizations and civil society from the global North and South, managed to stop it.

In 2000, the United Nations declared a moratorium against its experimentation and use that, accompanied by active social surveillance, was reinforced in 2006 and has not been able to be reversed or violated by any country. It thus became an exemplary case of “social evaluation of technology”. Despite being backed by some of the most economically powerful transnational corporations and governments in the world, GURTs could not advance due to social action, based on the damage it would be likely to bring. It is also an exemplary case of early warning and action based on the precautionary principle

2) l’ECID (Mali)

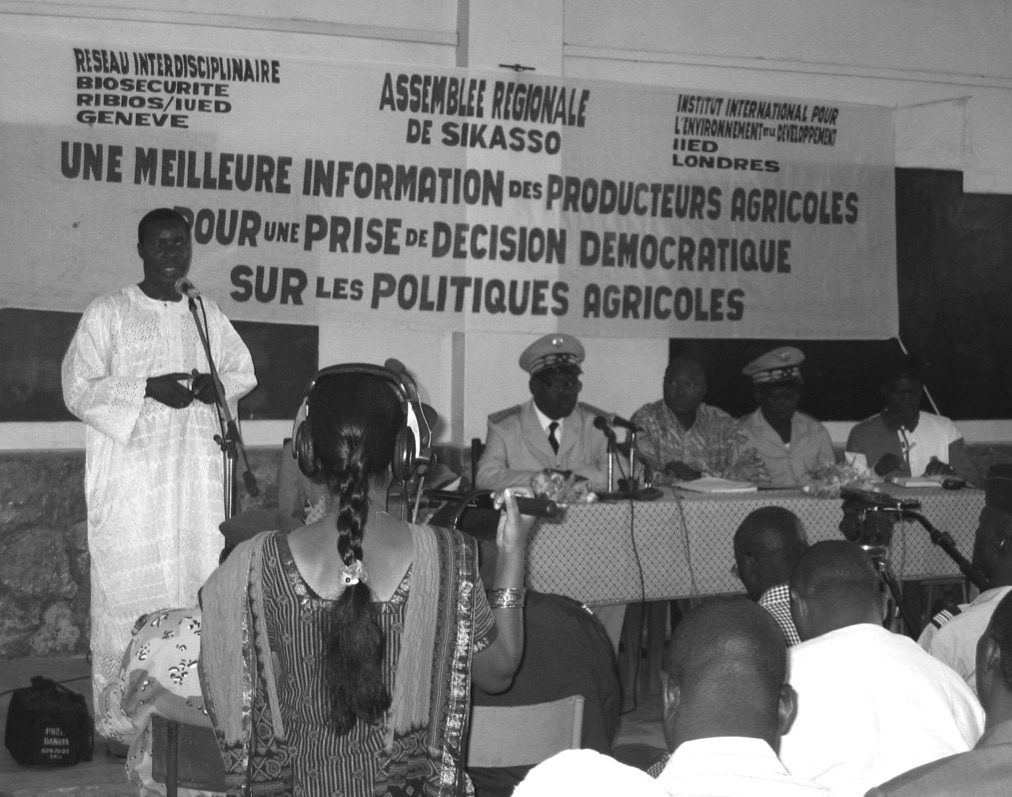

Towards the end of January 2006, 45 Malian farmers gathered in Sikasso to take part in a similar pTA to Prajateerpu – a citizens’ jury to deliberate the role of genetically modified (GM) crops in the future of the country’s agriculture.

This farmers’ jury was known as l’ECID (Espace Citoyen d’Interpellation Démocratique – Citizen’s Space for Democratic Deliberation). It set out to give farmers, who have been previously marginalised from policy-making processes, the opportunity to share knowledge, make a series of recommendations, and influence future policymaking.

It was an attempt to challenge the hegemony of pro-GM discourses being promoted among farmers in the region. The outputs of the jury process L’ECID amplified alternative viewpoints, the voices of those rarely asked for their opinions, and the perspectives of the people most profoundly affected by agricultural biotechnology.

L’ECID had a very real impact in Mali, both in terms of stimulating a national debate and ultimately in delaying the introduction of GM crops into the country.

3) Prajateerpu (India)

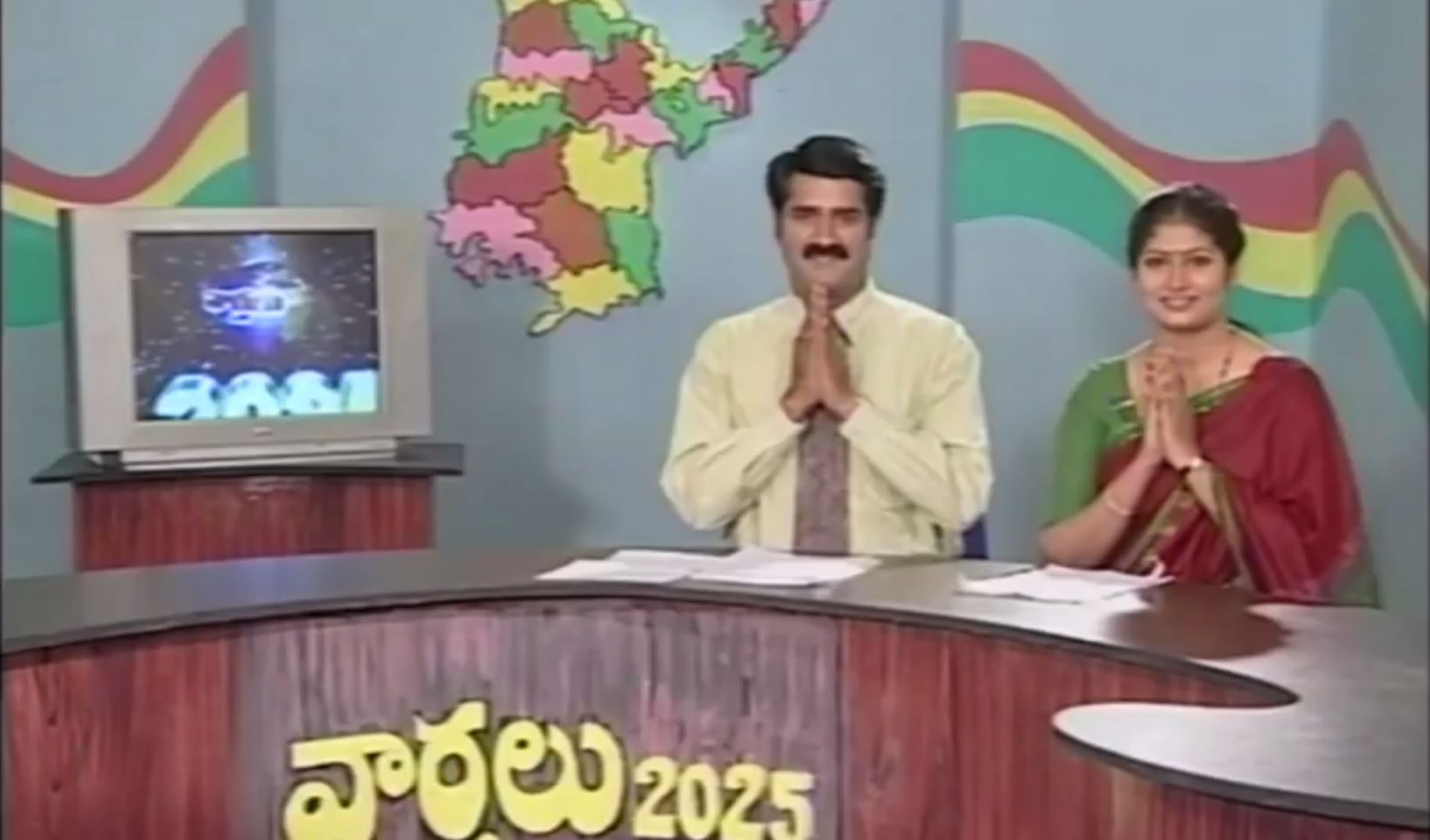

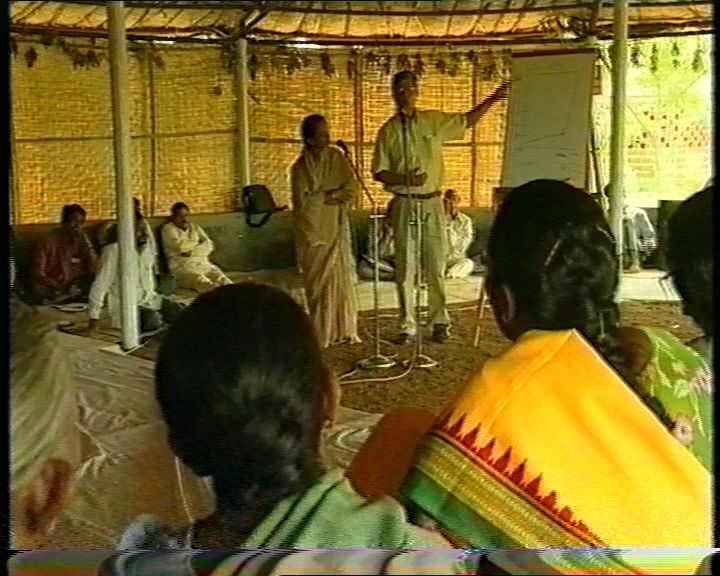

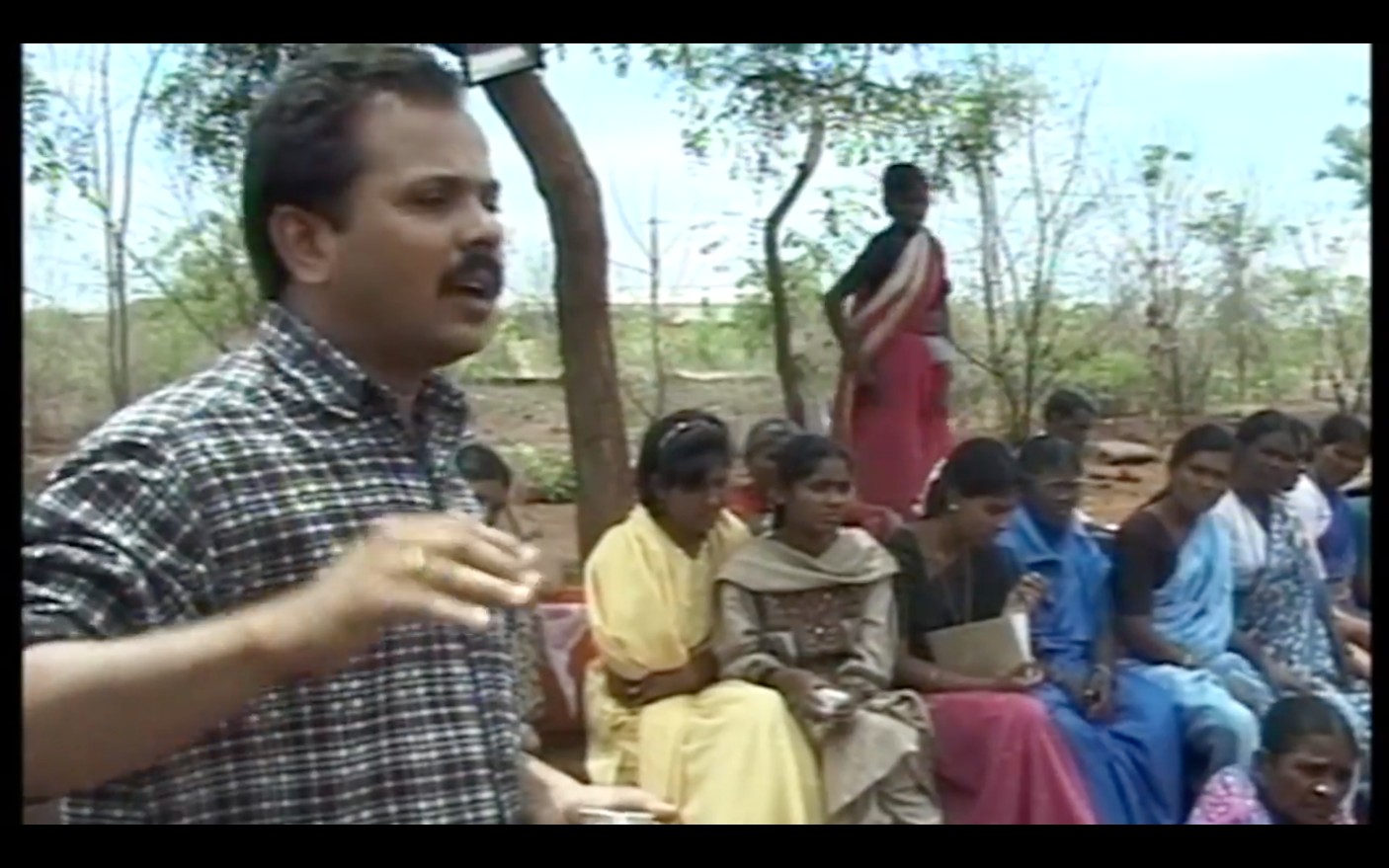

In response to an attempt, funded by the World Bank and Britain’s DFID, to displace farmers from land in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh via a strategy called Vision 2020, a coalition of Indian grassroots-led organisations and participatory action research (PAR) practitioners from India and the UK undertook Prajateerpu (‘people’s verdict’).

This was a hybrid approach merging elements of participatory technology assessment called a citizens’ jury and another methodology called the scenario workshop. The jury was made up of a majority of women farmers, with people from Dalit and Indigenous communities also in a majority.

At the time, Golden Rice, the marketing term used for rice that had been fortified with Vitamin A through genetic modification, was being promoted by the biotechnology industry as a pioneering way of addressing malnutrition. When an expert spoke in support of Golden Rice, the farmers pointed out that it was the very dominance of rice in the diet, to the exclusion of vegetables and pulses, that was threatening malnutrition, not the lack of Vitamin A alone.

Discussed in Parliaments in India and the UK, Prajateerpu had a long-lasting impact on how policy-makers viewed issues relating to smallholder farmers and new technologies – regionally, nationally, and internationally.

3 examples of citizens’ assemblies as technology assessment in Europe

A citizens’ assembly is a larger version of a citizens’ jury. Like a jury, it brings together a group of everyday people to learn, deliberate and agree recommendations on an issue. Random selection is often used to ameliorate the common tendency for political fora to favour those with higher socio-economic status and formal education. Advocates of citizens’ assemblies highlight their diverse membership compared to other political institutions. Like juries, citizens’ assemblies are often referred to as a ‘microcosm’ of society or a ‘mini-public’.

Because of their large size and the expenditure required to set them up, a citizens’ assembly is usually commissioned by a public authority. An advisory board comprised of a diversity of interests oversees the process to ensure that the framing of the issue, the evidence provided to participants and overall design is balanced and fair. Citizens’ assemblies generally include 50-100 participants and are run over a number of days.

Both citizens’ juries and assemblies can be an effective means of setting technologies in the broader context of ethical, social and economic issues. In an Irish citizens’ assembly, termination of a pregnancy (a procedure necessitating the use of a range of technologies) was set in the context of relevant social and ethical concerns. In France and the UK, citizens’ assemblies considering the need to reduce human contributions to climate change included reference to a range of technologies, including cars, aviation, renewable energy, biofuels and carbon-capture and storage.

1. Ireland

The Irish Citizens’ Assembly was made of 99 participants, ran over 12 weekends across 18 months and dealt with issues including the constitutional status of abortion, climate change and the challenges of an aging population.

In the case of women’s right to abortion the Assembly’s recommendations led to a national referendum, leading to a majority voting for a change in the law. It is not clear the extent to which the Assembly’s deliberations – as opposed to the activities of Irish feminist movements over many years –influenced the public who voted in the referendum.

Nevertheless, on abortion, the Government chose to act on the Assembly’s recommendations by holding the referendum. However much less has been delivered by the Government on either climate change or the challenges of an aging population.

2. France

A French citizens’ assembly process, “Citizen’s Climate Convention” (Convention citoyenne pour le climat) was established in October 2019 by the Economic, Social and Environmental Council at the request of Prime Minister Édouard Philippe. It brings together 150 citizens drawn by lot from among the French population. It aims “to define a series of measures that will allow to achieve a reduction of at least 40% in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 (compared to 1990) in a spirit of social justice.”

The convention was announced by the President of the Republic Emmanuel Macron in April 2019, to address the national protests and debate driven by the ‘yellow vests’ movement, which brought together citizens, activists and academic personalities.

In the convention’s report published in July 2020, the convention made 149 proposals. Macron has committed to applying all but three. These three are: a reformulation of the preamble to the Constitution; taxation of 4% on the dividends of companies with more than 10 million euros profit per year; and a 110 km/h speed limit on motorways. Both Greenpeace and Sciences Citoyennes have been critical of these omissions and of the apparent bias already shown by the Macron government’s implementation discussions, in which French aviation corporations have been over-represented. As with many processes led by a single powerful organisation, the danger is that the French government has co-opted (see glossary) the process falsely to give legitimacy to pre-existing policies.

3. UK

The Climate Assembly UK was a citizens’ assembly process running from 2019-20. It differed from the Irish and French processes in that it was commissioned by six Select Committees of the House of Commons, rather than the government and thus lacked a commitment to implement its conclusions.

The parliamentarians’ aim was “to understand public preferences on how the UK should tackle climate change because of the impact these decisions will have on people’s lives”. The assembly brought together 108 people from all walks of life, with a range of age, education, region, income, ethnicity, and climate change attitudes that reflect the diversity of the British public. The group spent 60 hours learning from experts on how climate policy and science will affect the UK. Then they were asked to propose a way forward.

The final ideas, which assembly members voted on, account for things like cost and difficulty – for example, in making radical changes to people’s lifestyles. The government has said it will study the citizens’ plan. Greenpeace UK argues that “although they won’t be forced to follow the recommendations, they’ve now got even more proof that the public is ready for bold actions to tackle climate change”.